Dear friends,

Let us introduce ourselves. We are Inside Out; a temporary school within The Glasgow School of Art.

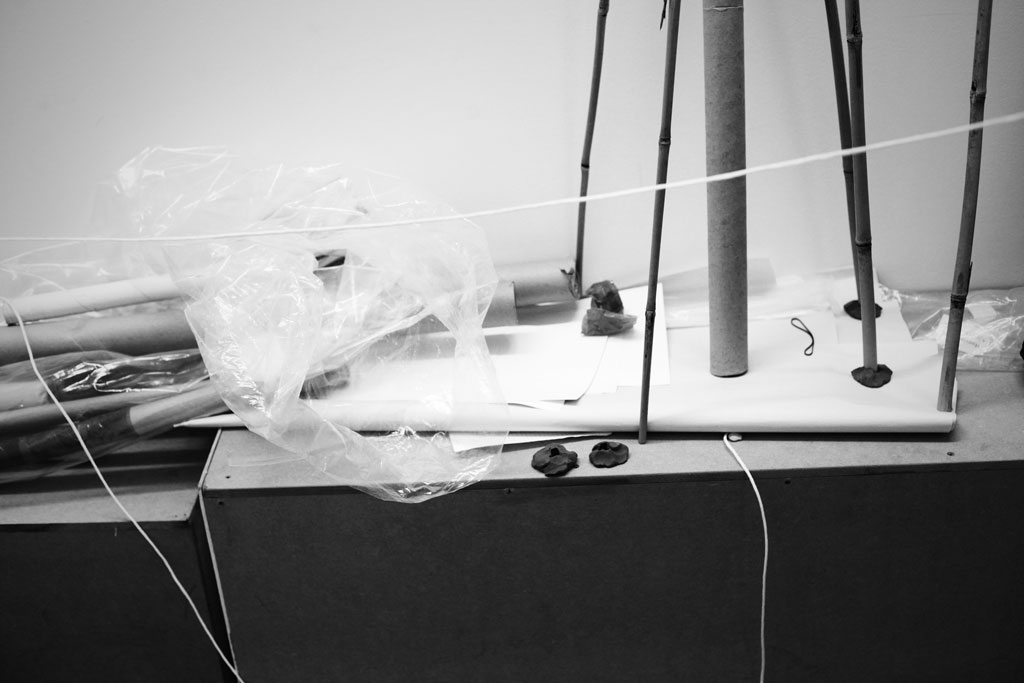

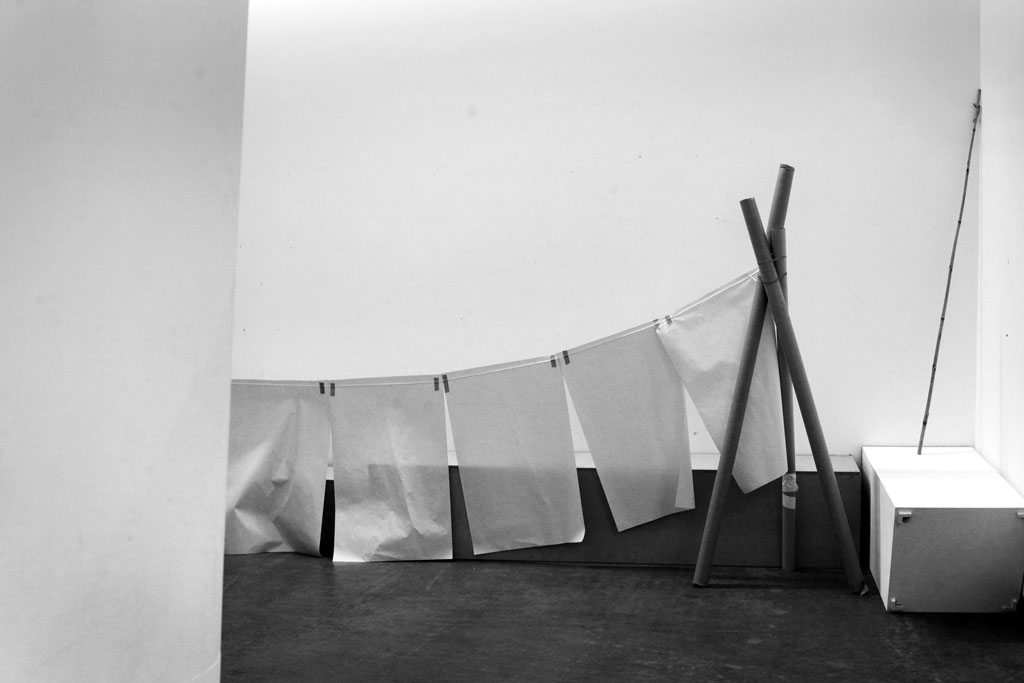

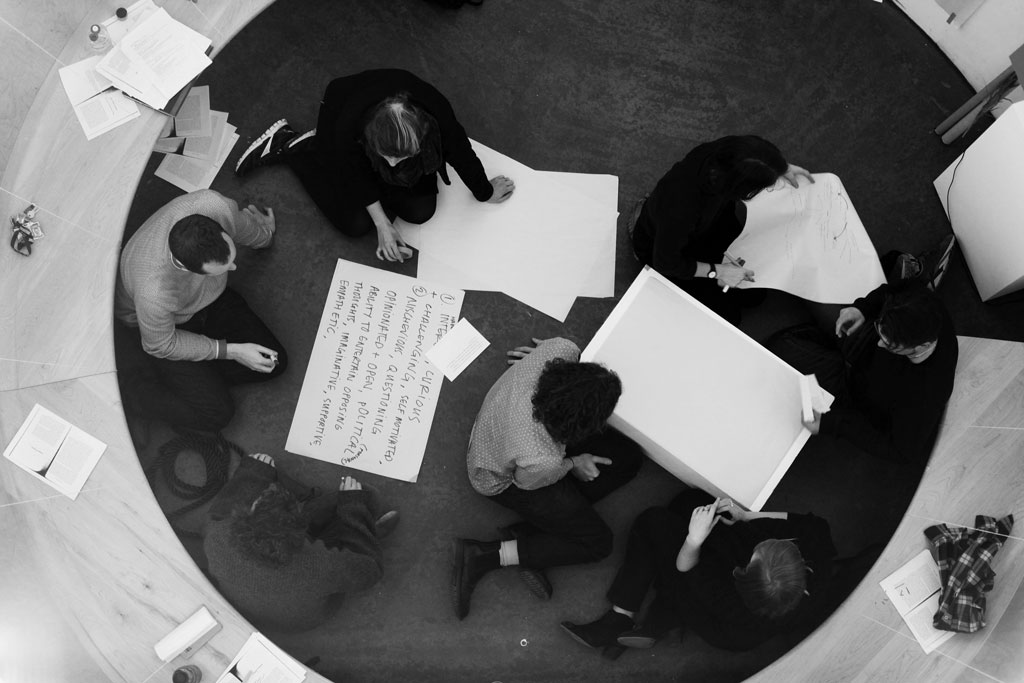

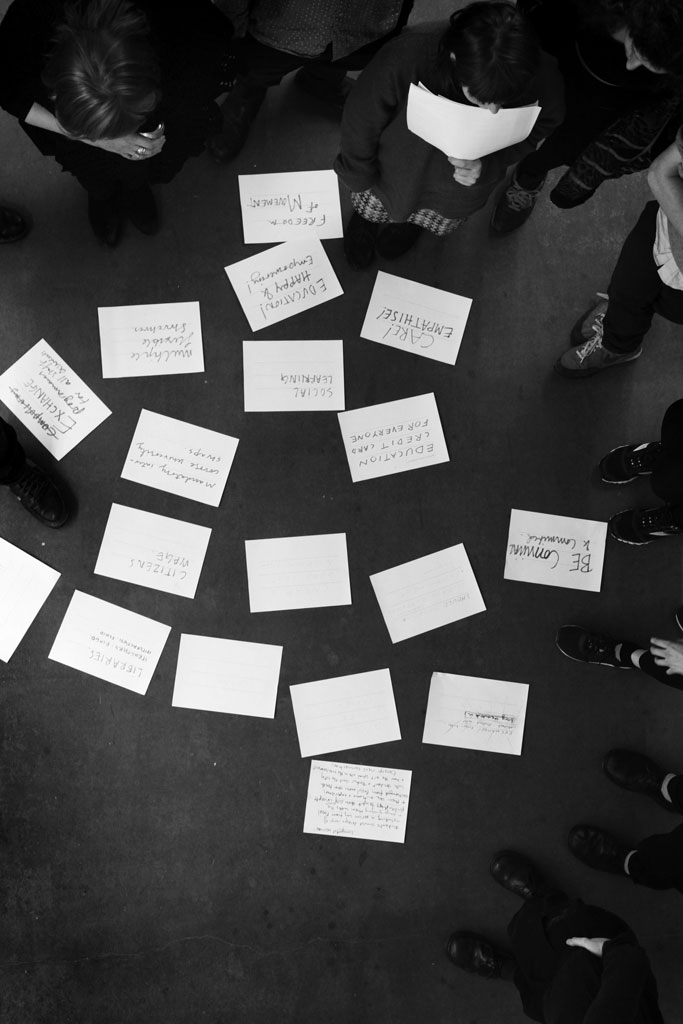

Inside Out assembled on 2nd December 2014 at The Glasgow School of Art in the corridors of the newly built School of Design. Our aim was to explore the tensions present within institutional education, more precisely, the tensions which exist between inside and outside art school. The activities we planned were intended to create discussion by manifesting these tensions in a series of symbolic and functional acts. The most basic of these was the displacement of work from the classroom into the corridors of the school. Chairs, tables and other objects were then assembled, modified and combined to create temporary partitions, seating and general infrastructure for the after-noon’s working groups. The idea of conflict as a methodology, as discussed by Markus Miessen and Chantal Mouffe [1], was a key reference point, as were past pedagogical projects such as The Antiuniversity [2] and Hidden Curriculum by Annette Krauss.[3]

As the final act of Inside Out, we are compiling a pamphlet on art and design education projects which will be available for free in print and online. It is an opportunity for us to share what we have learnt over the course of Inside Out, and collect the experience and advice of other education groups.

Endnotes

[1] The Nightmare of Participation By Markus Miessen. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010. Agonistics: Thinking The World Politically by Chantel Mouffe. London and

New York: Verso, 2013.

[2] The Antiuniversity of London was a short-lived and intense experiment into self-organised education and communal living that took off at 49 Rivington St.

in Shoreditch in February 1968. www.antihistory.org

[3] Annette Krauss, Hidden Curriculum, 2012.

Based on your experience, how do you view self-organised education, teaching and learning projects?

<Robert Preusse and Stefanie Rau>

The most interesting aspect of this question is hidden in the little word ‘self-’. Although studying at an art university usually requires a self-determined study structure, an overarching, institutional structure remains, and there is a huge difference between following this structure and actually creating your own by self-organising and determining alternatives. ‘Self-organised’ initiatives create a common space for exchange and reflection which stands outside of an accredited learning system that often isolates individuals: the shift of responsibilities, of decision making, and the setting of a framework for teaching and learning changes how one can act within this space in which possibilities and rules are negotiated and determined collectively.

<Jaime Iglehart> I view self-organized teaching as a crucial tool for world-making. In devising our own framework and our own classes, we create spaces of pure desire. Creating a pre-figurative space is almost like practicing dream work – we dream the dream of what we would like to see in our reality, and collectively we support and actualize these dreams in a kind of trial run or liminal space. These spaces are by definition marginal, unofficial, unaccredited. Open spaces such as free schools are laboratories both for the knowledge we wish to disseminate as content and experimentation within our classes, as well as the very process of protecting our spaces of learning as ‘safe spaces.’ Learning how to change together as a group and to deal with unwanted behavior is a necessary intertwined process.

What role do you think these projects play?

<Robert Preusse and Stefanie Rau> Self-organised initiatives can enable reflection on institutionalised education and initiate a change in attitudes towards it.

<Jaime Iglehart> I guess the question I would ask is, ‘What role do these projects play and in what context?’ The first session of the Utopia School took place in a DIY arts space, and I would say the role it played in that context was a transformative one – although ultimately limited in its powers of transformation on the scale of even such a small arts space. The Utopia School itself was occupying space within that arts collective, so the affect it had on the people actively involved in the school was something different to the affect it had on its host institution. The Utopia School is designed to be a nomadic project, landing for periods of time to gather a group of people together, and then moving on to the next space, so I think it’s only natural that the role of the school in the world at large is also of a nomadic nature. The main gifts which the first session of Utopia School brought to the world are more molecular in nature, forming strong relational connections and moments of realisation for people who participated. Since that session ended, many of the participants remain in close contact, working on separate projects together, traveling together, and so forth.

<Tyler Paige> Self-organized education experiments and projects have

given me a vantage point to look at the institutions I would otherwise not question. I think there are a lot of anxieties and feelings of oppression that happen within educational institutions that individuals often do not confront or even realize until they’re outside that institution. Within the institutions of which I’ve been a part, constantly being caught up in some sort of esprit de corps prevents time for reflection; and worse it prevents time to respect others’ reflections. My experience with institutions has shown me they tend to have strong momentums – for better or worse. When we organize our own educations, I’ve found that we can confront our institutions. We can choose to supplement them or we can choose to circumvent them.

<Eric Schrijver> For me, self-organised education projects are all about reframing the role of the individual in art and design. Like Robert and Steffi mention, art education isolates individuals – they are almost exclusively graded individually. A student is supposedly already busy constructing their body of work apart

from others.

This individualism continues after studies, especially in fine arts. You can see it in the way artists talk about what they do: in my work, in my practice, etc. Curators teach artists to talk this way. It is the logic of the market: to sell work, it has to be scarce, and objects made by a very special

individual are, by virtue of their creator being special, special themselves.

What is worrying in this, to me, is that artists spend too much time in trying to figure out how they are unique. They talk about their practice as some kind of sealed-off ecosystem. Yet if their work is going to have any impact - whether socially or emotionally – it is because their interests are not unique, but they are shared: shared with other artists, shared with the audience.

I don’t mean to negate individuality – I think an individual has agency, and the individual mind can be a fertile breeding ground where ideas mingle and new ideas, visions come to fruition. But the extent to which individuals can act upon their ideas is completely dependent on the links they have forged with the others around them.

Organising ones own education is a way of re-asserting that you care. You care about the people with which you think, work and exchange, and the structures that make this possible. And you take responsibility for these structures.

For the Inside Out school workshop, working from within an institution was a defining part of the project; it provided a critical framework and gave us access to resources that we would have otherwise struggled to find. In your opinion, what is the relationship of self-organised education projects, groups and movements to the Academy?

<Robert Preusse and Stefanie Rau> To have access to resources is

an important practical aspect, but it is also interesting to appropriate and adapt this space where usually other rules apply. To open and change conditions within the often highly exclusive space of art institutions, can create productive tensions and function as an integrative force in the Academy.

<Jaime Iglehart> The Utopia School was not intended as an alternative

or appendage to academia, but was intended to come out of the rich history of free and cooperative schools, particularly the practices of squatted social centres in London, such as the House of Brag. Because of the harsh anti-squatting laws in London currently, squatted social centres have had to move often. In response to this, the squatters decided to plan for a short occupation period, and therefore to spend months in advance planning a

program of workshops. The House of Brag is a squatted queer social centre, and was a huge inspiration to me in working on Utopia School. Being in an explicitly queer educational space opened a field of possibility to me. So, not only does the Utopia School hope to emerge from these traditions, but also to study them and pass on knowledge about their operational structure! On this front we are at the beginning.

If I were to draw connections between the Utopia School and academia, the connected dots would again come through the participants, some of whom work within academia and some of whom came to the school out of a disillusionment with their formal education. It has been of interest to keep the proliferation of academia-speak, and the tendency towards academic ‘debate’ (needlessly shredding each other’s perspectives rather than building on them – see David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology) more or less out of the Utopia School, and rather to keep it as a place where conflicting ideas can flourish.

<Tyler Paige> Personally, I associate working inside and outside of

existing institutions with having pretty different goals. When Free Cooper Union took over the college president Jamshed Bharucha’s office, we set up an exhibition that was at once part of and separate from the yearly Cooper Union End of the Year Show (EOYS). The yearly show Show Up occupied the bottom six floors of the building, while our Step Down (one big yikes to both titles) took the top floor. Show Up organized work into supposed disciplines: painting, printmaking, photography, video, sculpture, architecture. Step Down, by

contrast, attempted to acknowledge that virtually none of us was working exclusively in these disciplines; and so we tried to mix all of these things. We invited artists, writers, activists, etc. to present ideas and conversations, with this blackboard that seemed to follow us wherever we went. All

of that sort of made a little school inside of the school. But mostly the purpose of that parasite school was directed towards rethinking its context: the larger institution. Of course, there were lessons there that extended into all of our individual practices – like a few students who came out of Free Cooper Union and are now bringing in voices that are otherwise absent from our school – but largely we were gathered for the sake of Cooper

Union itself. I mean, we were totally a parasite. We used Cooper’s space, piggybacked off their exhibition’s publicity, and took advantage of their foot-traffic.

But with the project space I’ve been running with my best friend and roommate, David Johnson, our eyes are focused somewhere else. We are still finding ourselves having a loosely organized ‘school’ (writing workshops, crit club, activist presentations, and soon some computer classes), but these things are less centralized around an existing structure. Working outside of Cooper Union has allowed us to avoid so much focus on rethinking or fixing. We’ve adopted an attitude of making these school-type projects necessarily shortterm and shape-shifting; and we hope that lets us constantly improve. I don’t think this is something we could have accomplished inside of a place that

has been around since 1859.

In our experience pedagogy projects are exhaustive in the way that they work – they are driven by intensive bursts of activity – this can be positive but also limiting. In your view, which ways of working or

organisational structures have achieved their objective?

<Robert Preusse and Stefanie Rau> There is no failing in experiments, every effort enables learning and furthers understanding. For us, Parallel School has been successful in creating an inspiring space for a limited amount of time. Our engagement in Parallel School has had a big influence on the relationships we have formed. It has effectively changed our attitude towards the academy and the way we study. In this sense, we think it has achieved the objective of empowering students.

<Jaime Iglehart> There are many examples of free and experimental schools which have had a positive impact on the people involved. I think ‘a positive impact’ is the only measure of success, and it is a completely subjective measurement. In the US, state schools have standardized tests

to measure successful education, but these tests are a complete abomination. Free and experimental schools, must follow a different logic. In a subjective measurement, only the people involved with the project can say whether it was worth their time. If enough people say it was worthwhile to continue the project or to spawn another, then it must have been a success.

A more concrete example of a success story might be Paideia, an anarchist free school for and run by children located in Merida, in southwest Spain. The school is famously difficult to gain access to, but there is a wonderful account of it in the recent publication, Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education.

<Tyler Paige> Kind of following from my last comments about shape-shifting, we’ve found that the ability to fluidly change structures is vital. When structures become unaccommodating or inflexible, the structure is no longer helpful and it needs to change. If I knew which type of organization worked best, I would gladly tell; but ultimately it is too complex for a prescription. I will say I am bit sceptical of the Occupy-type organizations that seem to get haphazardly reproduced everywhere because I think they convince people that there is more horizontalism than in actuality. But as a general rule, I’ve found that an almost puritanical level of documentation helps things run smoothly. Having a record of organization and why things are organized in such a way – as well as having that record easily accessible – will help everyone stay on the same page. Importantly, it will also help people who are new.

<Eric Schrijver> For artists and designers, it can be highly refreshing to get to know communities in which self-organised learning and collaboration are the norm. For me this was the case with the Free and Open Source Software movement.

In an institutional education framework the roles can be quite fixed. A teacher is a teacher, a student a student. In Free Software, the role is context-dependent. If you start a project, you are tacitly considered the ‘lead developer’, the person with the vision for where the project should go, and people who contribute to the project are at first more like helping hands. Yet these contributors might have their own projects where they are

the lead developer. And these roles then shift over time.

Art schools that favour such an approach do seem to exist. For some time the artists coming out of the institutional framework of DASarts in Amsterdam would be people constantly working on each others’ projects, but shift roles: they’d act in a piece one of their colleagues directed, and vice versa. But these are exceptions to what I’ve seen.

So as to the role, then, of these self-organised pedagogy projects: I think they can adapt alternative approaches to collaboration and education as found, for instance, in Free and Open Source Software, and make them function in the context of art and design. Of course they do not have the resources to make it last for years, with thousands of people – maybe it is just one week. But you hope that some germs spread, some ideas infect.

What advice would you give someone who wants to organise an

education project in their school or community?

<Robert Preusse and Stefanie Rau> We don’t know if we are in a

position to ‘give advice’. Of course experience is the best teacher but we think we can still learn a lot from each other. Projects like 'the TEACHABLE FILE' have been useful but also the legacy and documentations of past Parallel Schools have helped us a lot to start our own journey into the topic. This is why we try to document our activities, so we can leave traces and allow others to adopt and learn from them. Parallel School is an open format that can and should be picked up and continued.

<Jaime Iglehart> Find a free or experimental school/class to attend and visit it. There are lots of initiatives already taking place. If you live near a major city, chances are there is something going on. Do a little research and see if you can meet some people who are already trying it out. If no one is studying what you want to study, try to find a local community or arts space/collective that you appreciate. Decide what you want to study (maybe a cyborg feminist reading group, for example?). Promote your activity through the space’s list-server and other social media, do some flyering in the neighborhood (laundromats, cafés, bookstores) and see how it goes!

<Tyler Paige> It seems right to underscore Jaime Iglehart here: seek out the work that others may be doing. People are experimenting in many cities. It’s important to recognize that many educational and pedagogical projects are the results of conversations and collaboration inside and between groups. If nothing else, some experience with others’ projects may help demonstrate what a new project could look like. ¶